Wallace Rice on Chicago Stars

From a 1928 letter by Wallace Rice to a Mr. Ettleson:

To return to the six-pointed stars in the Chicago municipal flag. By the terms of the competition under the rules laid down by the Chicago Flag Commission in 1917, the use of religious symbols, which included the cross, the star and crescent, and the two triangles, one reversed and superimposed, was barred, for obvious reasons. [1] The five-pointed star, symbol of a soverign State, was also considered out of place, for reasons which I hope have been made equally obvious here. Chicago is a city.

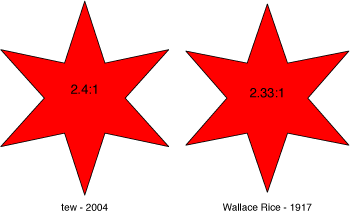

After more than four hundred designs had been made by me, I finally struck upon such a six-pointed star as had never appeared in any flag before, peculiarly and singularly a Chicago star, made by a Chicagoan for his greatly loved city, by an American in the tenth generation in this country, whose ancestors had fought against Great Britain, for the most American of American cities. It differs from all other stars in use in European heraldry and in State and National flags and coats-of-arms, and is specifically for and of Chicago and nowhere else on earth because its points are straight and not like the usual heraldric etioile curved like flames, and because these points subtend an angle of only thirty degrees, instead of the sixty degrees subtended in the star made by superimposing a triangle.

- According my copy of the rules, on file at the Chicago Public Library’s municipal reference collection, no rule specifically bars religious imagery.